ACID compliance in data analytics platforms: what it is, why it matters, and how to verify it (2026)

TL;DR

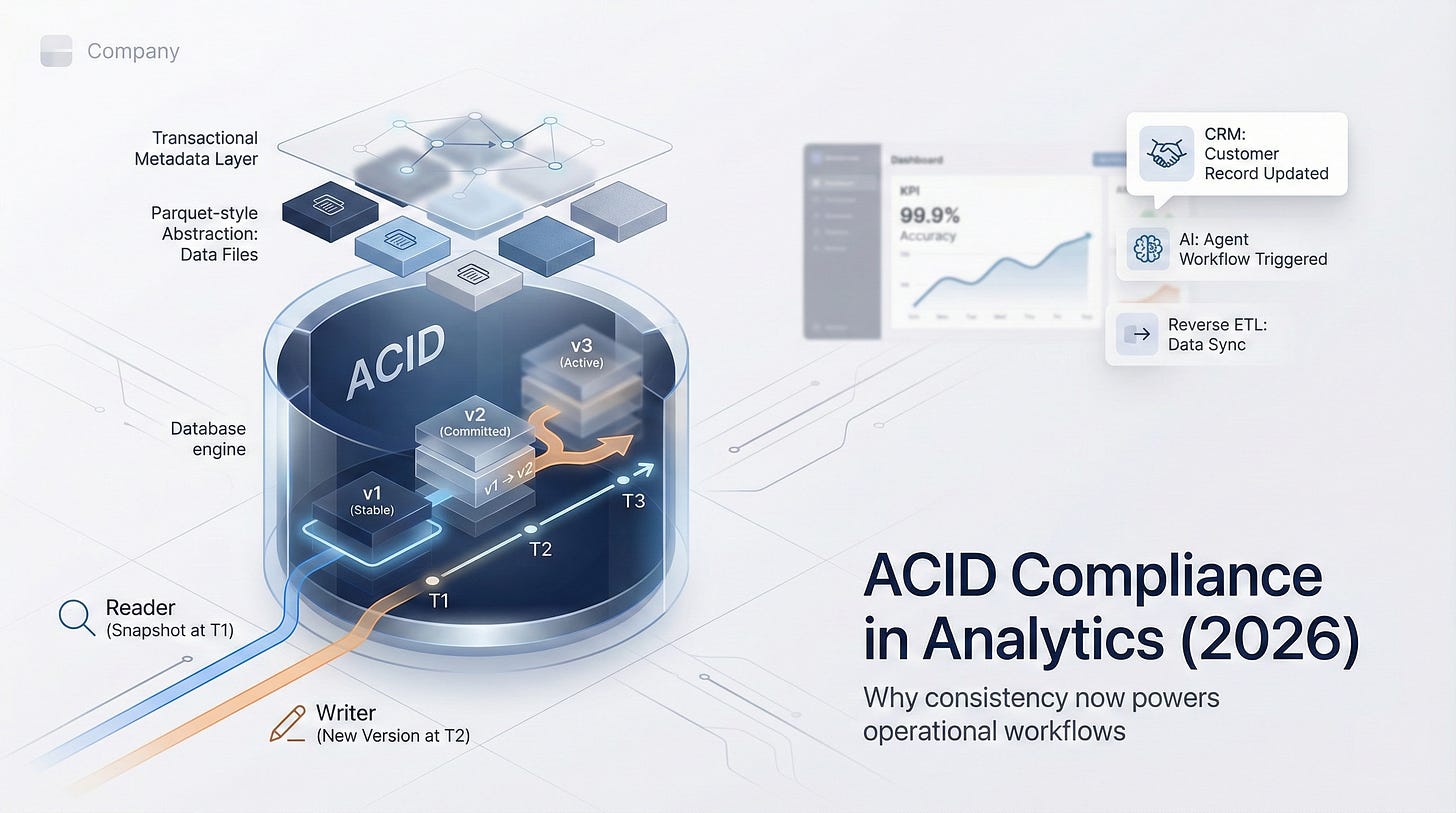

ACID matters in 2026 analytics because warehouses now power operational workflows (Reverse ETL, AI agents, user-facing apps). Dirty reads and inconsistent snapshots become real business incidents.

ACID is enforced via MVCC + isolation levels + a transactional metadata layer (the “ACID” often happens in metadata, not in data).

Most cloud warehouses optimize for concurrency and may default to weaker isolation (often READ COMMITTED), which can cause anomalies in multi-step transformations.

Lakehouse table formats (Iceberg/Delta) can be ACID, but pay a “maintenance tax” (small files, compaction/vacuum, metadata bloat).

Scale-up/hybrid engines (DuckDB/MotherDuck) deliver fast commits and strong consistency by keeping transaction management close to compute (WAL/MVCC) and avoiding distributed metadata latency.

Trust but verify: run dirty read, lost update, recovery, and “surprise bill” micro-transaction tests to validate correctness and cost.

You’ve probably stared at a dashboard where the “Total Revenue” KPI didn’t match the sum of the line items below it. Or maybe you’ve debugged a “Single Source of Truth” table that mysteriously dropped rows during a high-traffic ingestion window.

In the past, we called these glitches and moved on. We accepted that the analytical data were eventually consistent because it was historically backward-looking. A report generated at midnight didn’t need to reflect a transaction that happened at 11:59:59 PM.

But in 2026, “good enough” consistency is dead. Analytics isn’t a read-only discipline anymore.

Data warehouses now power operational workflows via Reverse ETL, feed live AI agents, and serve user-facing analytics in real-time applications. When a warehouse drives a marketing automation tool or a customer-facing billing portal, a “dirty read” isn’t just a glitch. It’s a compliance violation, a lost customer, or a triggered support incident.

This guide goes beyond the textbook definitions of Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability. We’ll look at how modern platforms, from decoupled cloud warehouses like Snowflake to open table formats like Iceberg and hybrid engines like MotherDuck, mechanically guarantee trust. We’ll dig into the hidden costs of these architectures and give you a framework for verifying that your “Single Source of Truth” isn’t actually a lie.

Why ACID compliance matters for modern analytics (and how it works)

The “Big Data” era trained us to accept eventual consistency. When you processed petabytes of logs with Hadoop, the count could be off by 1% for a few hours. Those systems were designed for massive throughput, not transactional precision.

But the “Big Data” hangover has cleared. We’re facing a new reality: Operational Analytics.

Tools like dbt (data build tool) and Reverse ETL platforms have transformed the data warehouse from a passive closet into an active nervous system. Pipelines now target freshness windows of 1 to 60 minutes. Marketing activation and sales operations demand data that’s accurate right now.

If your warehouse feeds a CRM, and that CRM triggers a “Welcome” email based on a signup event, the underlying storage layer must guarantee that the signup record is fully committed and visible before the email trigger fires. You can’t have reliable Data Governance or a semantic layer if the underlying storage can’t guarantee atomic commits. Without ACID, your “governed metrics” are just suggestions subject to race conditions.

How MVCC enables ACID compliance (and what isolation levels mean)

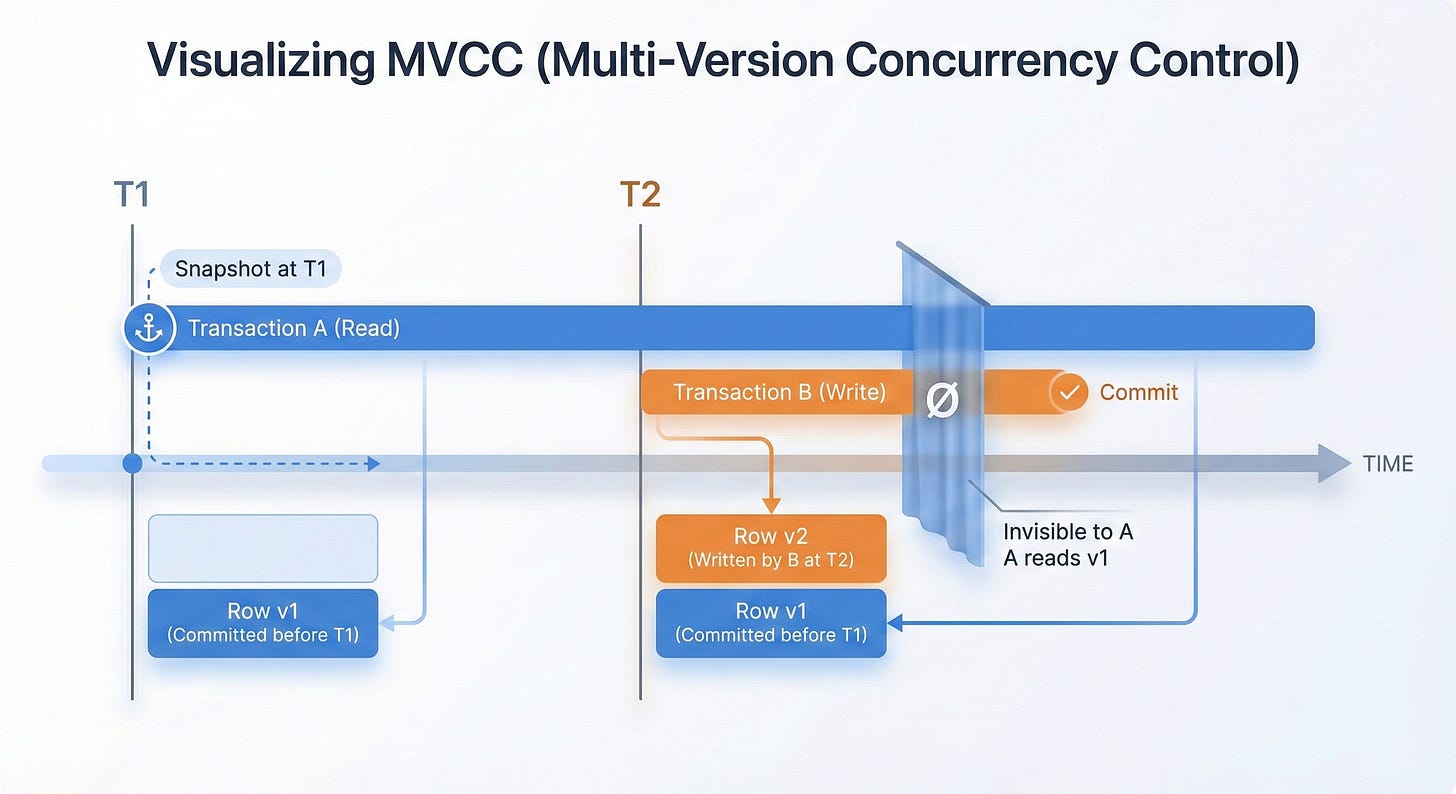

To understand how modern platforms solve this problem, we need to look beyond the acronym and examine the implementation standard: Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC).

DuckDB, Snowflake, and Postgres all use MVCC to handle high concurrency without locking the entire system. In a naive database, a writer might lock a table to update it, forcing all readers to wait. In an MVCC system, the database maintains multiple versions of the data simultaneously.

The Reader: When you run a SELECT query, the database takes a logical “snapshot” of the data at that specific moment. You see the state of the world as it existed when your query began.

The Writer: When a pipeline runs an UPDATE, it creates a new version of the rows (or files) rather than overwriting the old ones.

This versioning lets readers and writers coexist without blocking each other. But MVCC alone isn’t enough. The database must also enforce Isolation Levels. Isolation isn’t a binary “on/off” switch. It’s a spectrum of guarantees that trades performance for correctness.

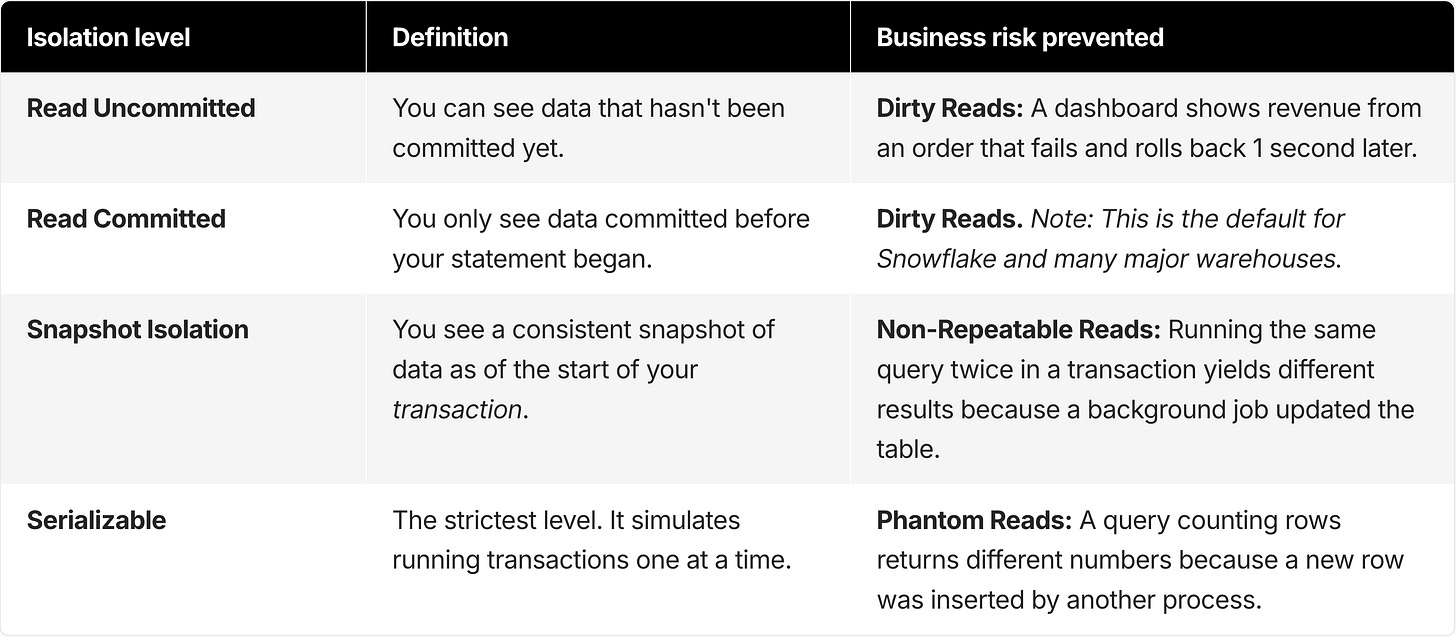

Isolation levels explained: read uncommitted vs read committed vs snapshot vs serializable

Different business risks map to different isolation levels. Understanding this hierarchy is critical for evaluating platforms, since many cloud warehouses default to lower levels to maximize concurrency.

Snapshot Isolation and Serializable offer stronger guarantees, but they come with performance costs. Many decoupled cloud warehouses, including Snowflake, support READ COMMITTED for standard tables.

This isolation level means that if you have a multi-statement transaction (say, a dbt model with multiple steps), two successive queries within that same transaction could return different results if a separate pipeline commits data in between them. For complex transformation logic, READ COMMITTED can introduce subtle, hard-to-debug data anomalies.

Where ACID actually happens: the metadata transaction layer

If the data files (Parquet, micro-partitions) are immutable, where does the “ACID” actually happen? In the metadata. The difference between a loose collection of files and a database table is a transactional metadata layer that tells the engine which files belong to the current version.

In Cloud Warehouses (Snowflake/BigQuery): A centralized, proprietary metadata service acts as the “brain.” It manages locks and versions. Snowflake, for example, uses FoundationDB (a distributed key-value store) to track every micro-partition.

In Table Formats (Iceberg/Delta/DuckLake): The file system (S3/Object Storage) combined with a catalog acts as the source of truth. They rely on atomic file swaps or optimistic concurrency control to manage versions.

In Scale-Up Engines (DuckDB/MotherDuck): Transaction management is handled in-process using a Write-Ahead Log (WAL). Because the compute and transaction manager are tightly coupled, commits are near-instant. No network latency from external metadata services.

Three ways analytics platforms implement ACID compliance (2026)

There’s no single “best” way to implement ACID. Three dominant architectures prevail, each optimizing for a different constraint: scale, openness, or latency.

Approach 1: Decoupled scale-out warehouses (Snowflake, BigQuery)

This architecture separates storage (S3/GCS), compute (Virtual Warehouses), and global state (The Cloud Services Layer).

How decoupled warehouses provide ACID compliance

When you run an UPDATE in Snowflake, you’re not just writing data. You’re engaging a sophisticated, centralized brain. This metadata service (backed by FoundationDB) coordinates transactions across distributed clusters. The service ensures that when your query completes, the pointer to the “current” data is updated atomically.

Pros of decoupled warehouses

Massive Concurrency: Because the metadata layer is distributed, these systems can handle petabyte-scale workloads where thousands of users query the same tables simultaneously.

Separation of Concerns: You can scale compute up and down instantly without worrying about data corruption.

Cons of decoupled warehouses: latency, cost, and weaker isolation

Centralizing the “brain” introduces friction. Every transaction, no matter how small, requires a round-trip network call to this central service. This imposes a “latency floor” on operations. You can’t simply “insert a row.” You must ask the global brain for permission, write the data, and then tell the brain to update the pointer.

This architecture also introduces a specific cost-model risk: Cloud Services Billing. In Snowflake, you’re billed for the “brain’s” work if it exceeds 10% of your daily compute credits.

Workloads that involve frequent “micro-transactions” (like continuous ingestion or looping single-row inserts) can thrash the metadata layer. This leads to “surprise bills” where the cost of managing the transaction exceeds the cost of processing the data.

And relying primarily on READ COMMITTED isolation means that applications requiring strict multi-statement consistency (such as financial ledger balancing within a stored procedure) need careful design. Otherwise, you’ll hit anomalies where data changes mid-execution.

Best for: petabyte-scale batch analytics

Petabyte-scale, “big data” batch processing where the engineering team manages complex infrastructure. This architecture works well when predictable costs are secondary to querying enormous datasets, and when the latency of individual transactions matters less than overall throughput.

Approach 2: Open table formats and lakehouses (Iceberg, Delta Lake)

This approach tries to bring ACID to the data lake without a proprietary central brain.

How iceberg and delta lake provide ACID transactions

Instead of a database managing the state, the state is managed via files in object storage (S3).

Delta Lake uses a transaction log (_delta_log) containing JSON files that track changes.

Iceberg uses a hierarchy of metadata files (Manifest Lists -> Manifests -> Data Files) and relies on an atomic “swap” of the metadata file pointer to commit a transaction.

Concurrency is handled via “Optimistic Concurrency Control” (OCC). A writer assumes it’s the only one writing. Before committing, the writer checks if anyone else changed the file. If a conflict exists, the writer fails and must retry.

Pros of open table formats

Vendor Agnostic: Your data lives in your S3 bucket. You can read it with Spark, Trino, Flink, or DuckDB.

Cost Control: You pay for S3 and your own compute, avoiding the markup of proprietary warehouses.

Cons of lakehouses: the small file problem and the maintenance tax

Relying on object storage creates a severe “Small File Problem.” Every time you stream data or run a small INSERT, you create new data files and new metadata files.

Here’s a real-world example. An Iceberg table with a streaming ingestion pipeline created 45 million small data files. This pipeline generated over 5TB of metadata alone (manifest files tracking the data).

When analysts tried to query the table, the query planner had to read gigabytes of metadata just to figure out which files to scan. Query planning times jumped from milliseconds to minutes, and the coordinators frequently crashed due to Out-Of-Memory (OOM) errors.

To make this architecture work, you have to pay a “maintenance tax.” You need to run compaction jobs (rewriting small files into larger ones) and vacuum processes (deleting old files) continuously. If you neglect this hygiene, performance degrades exponentially.

Best for: open data lakes with strong engineering support

Large-scale data engineering teams that prioritize open standards and have the operational capacity to manage the “maintenance tax.” This architecture fits well for massive batch jobs, but struggles with the latency and complexity of high-frequency operational updates.

Approach 3: Scale-up and hybrid engines (DuckDB, MotherDuck)

This architecture rejects the premise that you need a distributed cluster for every problem. It uses a “Scale-Up” approach (using a single, powerful node) coupled with a hybrid execution model.

How DuckDB and MotherDuck provide ACID compliance (MVCC + WAL)

DuckDB (and, by extension, MotherDuck) implements ACID using strict MVCC and a Write-Ahead Log (WAL), similar to Postgres but optimized for analytics.

Local: On your laptop, the transaction manager runs in-process. Network overhead disappears.

Cloud: MotherDuck runs “Ducklings” (isolated compute instances).

Why DuckLake improves metadata transactions for analytics

MotherDuck introduces a hybrid table format called “DuckLake”. Unlike Iceberg, which requires scanning S3 files to find metadata (slow), DuckLake stores metadata in a high-performance relational database (fast), while the data remains in open formats (Parquet) on S3.

Result: Metadata operations (checking table structure, finding files) take roughly 2 milliseconds, compared to the 100ms–1000ms “cold start” penalty of scanning object storage manifests.

Pros of scale-up engines: interactive speed and simpler transactions

ACID guarantees are handled in-process. Commits happen in milliseconds because no distributed consensus algorithm delays them. “Noisy neighbor” issues disappear because tenancy is isolated. You get the strict consistency of a relational database with the analytical speed of a columnar engine.

Cons of scale-up engines: not designed for 100+ pb single tables

This architecture isn’t designed for the 100+ PB single-table workload. It optimizes for the 95% of workloads that fit within the memory and disk of a large single node (which, in the cloud, can be massive).

Best for: operational analytics, interactive bi, and real-time dashboards

“Fast Data” workloads: user-facing applications, interactive BI, and real-time dashboards where sub-second response times are critical. Scale-up engines are the undisputed choice for local development and CI/CD, since they let engineers run full ACID-compliant tests on their laptop that perfectly mirror production behavior.

How to verify ACID compliance: a practical test framework

Marketing pages are easy to write. Distributed consistency is hard to build. Don’t just trust that a platform is “ACID compliant.” Verify the behavior, especially if you’re building customer-facing data products.

Here’s a framework of tests you can run in your SQL environment.

Test 1: How to test for dirty reads

Objective: Ensure that a long-running query doesn’t see uncommitted data from a concurrent write.

Session A (The Writer): Start a transaction. Insert a “poison pill” row (e.g., a row with ID = -999). Don’t commit yet.

BEGIN;

INSERT INTO revenue_table (id, amount) VALUES (-999, 1000000);

-- Hang here. Do not commit.

Session B (The Reader): Immediately query the table.

SELECT * FROM revenue_table WHERE id = -999;

Result: If Session B returns the row, the system allows Dirty Reads (fail). If Session B returns nothing, the system enforces isolation.

Finish: Commit or Rollback Session A.

Test 2: How to test for lost updates (concurrency)

Objective: See how the system handles two users trying to update the same row at the exact same time.

Setup: Create a table with a single row:

Counter = 10.Session A:

BEGIN; UPDATE table SET Counter = 11;(Don’t commit).Session B:

BEGIN; UPDATE table SET Counter = 12;(Try to commit).Result:

Blocking: Session B might hang, waiting for A to finish (common in lock-based systems like Snowflake).

Error: Session B might fail immediately with a “Serialization Failure” or “Concurrent Transaction” error (common in Optimistic systems like DuckDB/Lakehouse).

Silent Overwrite (Failure): If both succeed and the final value is 12 (or 11) without warning, you have a “Lost Update” anomaly.

Test 3: How to test atomicity and durability (recovery)

Objective: Verify Atomicity and Durability.

Action: Start a massive INSERT statement (e.g., 10 million rows).

Disruption: Kill the client process or force a connection drop halfway through.

Check: Reconnect and query the table.

Result: You should see zero rows from that batch. If you see 5 million rows, Atomicity failed. The system must use its WAL (Write Ahead Log) to roll back the partial write upon restart.

Test 4: How to measure the cost overhead of ACID transactions

Objective: Verify the cost of ACID overhead.

Action: Write a script that performs 10,000 “micro-transactions” (inserting 1 row, committing, repeating).

Check: Look at the billing metrics for that specific time window.

In Snowflake, check the CLOUD_SERVICES_USAGE metric. Did it spike above 10% of compute?

In BigQuery, check the API costs for streaming inserts.

In MotherDuck, verify that the cost remains flat (compute-based) and does not include hidden metadata fees.

Common ACID compliance mistakes in analytics platforms

Even with a compliant platform, implementation details can break your data trust.

Mistake 1: Assuming ACID means serializable isolation

Many engineers assume “ACID” means “Serializable” (perfect isolation). It usually doesn’t.

If you’re building a financial reconciliation process on a warehouse that defaults to READ COMMITTED, you need to manually manage locking or logic to prevent anomalies. Don’t assume the database handles complex race conditions for you.

Mistake 2: Treating object storage (S3) like a transactional database

Trying to implement ACID manually over raw object storage is a recipe for disaster. Developers sometimes think, “I’ll just write a file to S3 and then read it.”

Without a table format (like Iceberg) or an engine (like DuckDB) to manage the atomic commit, you will eventually hit eventual consistency issues, partial writes, or race conditions. S3 is now strongly consistent, but it doesn’t support multi-file transactions natively.

Mistake 3: Using a warehouse for micro-transactions (and overpaying)

Look, using a hammer to drive a nail is expensive.

We often see teams using massive cloud warehouses for high-frequency, low-volume updates (such as updating a user's “last login” timestamp). The overhead of the distributed transaction coordinator (latency + cost) outweighs the value of the data update. These workloads belong in an OLTP database or a lightweight engine like DuckDB that handles micro-transactions efficiently.

Mistake 4: Skipping compaction and vacuum in lakehouses

In Lakehouse architectures (Iceberg/Delta), “deleting” a row doesn’t actually delete it. It writes a “tombstone” or a new version of the file. Over time, your table becomes a graveyard of obsolete files.

If you don’t automate VACUUM and compaction, your read performance will degrade until queries time out. Managed engines like MotherDuck handle this hygiene automatically in the background.

Conclusion: Choosing the right ACID architecture for operational analytics

ACID compliance is the bedrock of trust in modern analytics. When a dashboard number changes every time you refresh, or when a high-value customer receives a duplicate email due to a race condition, trust in your data team evaporates.

The shift to operational analytics means you can’t rely on the “eventual consistency” of the past. But you don’t need to over-engineer your solution either.

For the 1% of workloads that are truly petabyte-scale, decentralized architectures like Snowflake or carefully managed Lakehouses are necessary, despite their latency and cost premiums.

For the 99% of workloads that deal with “medium data” (Gigabytes to Terabytes), the future is Scale-Up ACID.

You don’t need a massive distributed cluster to get banking-grade transactional integrity. You need an architecture that respects the physics of data. Keep compute close to storage and handle transactions in-process rather than over the network.

The Hybrid Advantage: If you want ACID guarantees that move at the speed of interactive analytics, without the administration of a Lakehouse or the latency of a distributed warehouse, evaluate MotherDuck. MotherDuck brings the power of DuckDB to the cloud, handling concurrency, consistency, and metadata automatically. It lets you build pipelines that are robust enough for operations but simple enough to run on your laptop.

In 2026, the “Single Source of Truth” shouldn’t be a lie. Make sure your platform can keep its promises.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does ACID compliance mean in an analytics platform?

ACID means transactions are atomic, keep data consistent, are isolated from concurrent work, and are durable after commit. In analytics platforms, ACID ensures that dashboards and downstream apps do not see partial writes or inconsistent snapshots during ingestion and transformations.

Is “ACID compliant” the same as “Serializable isolation”?

No. ACID includes isolation, but platforms can implement different isolation levels. Many systems are ACID by default, using READ COMMITTED or SNAPSHOT rather than full SERIALIZABLE.

What isolation level do major cloud warehouses typically use by default?

Many cloud warehouses default to READ COMMITTED for standard workloads, prioritizing concurrency. If you need repeatable results across multiple statements, you must confirm that stronger isolation is supported and how it’s configured.

How can I quickly test whether my warehouse allows dirty reads?

Open two sessions: in Session A, insert a row inside a transaction without committing. In Session B, query for that row. If Session B can see the row, the system allows dirty reads and fails the test.

How do Iceberg/Delta Lake provide ACID on object storage?

They commit changes by writing new data/metadata files and then atomically updating the table’s metadata pointer/log. Concurrency is typically handled with optimistic concurrency control (OCC), where conflicting writers must retry.

What is the “small file problem,” and why does it hurt ACID lakehouses?

Frequent small writes create huge numbers of small data and metadata files. Planning a query can require scanning large metadata structures, increasing latency, and sometimes causing coordinator memory failures unless you run compaction/vacuum regularly.

Where does ACID “actually happen” if my data is stored as Parquet files?

In the transactional metadata layer that decides which files are part of the current table version. The data files are often immutable. Correctness comes from atomically updating metadata and enforcing concurrency rules.

What’s the fastest way to validate durability and atomicity?

Start a large insert, then kill the client/connection mid-write. After reconnecting, you should see all or nothing from that transaction. Never a partial batch.

Why can ACID features increase costs in decoupled warehouses?

Distributed metadata coordination adds overhead per transaction (latency + metastore work). High-frequency microtransactions can trigger unexpected “control plane” or metadata-related charges, depending on the vendor’s billing model.

When should I choose a scale-up/hybrid engine instead of a lakehouse or distributed warehouse?

Choose scale-up/hybrid when you need interactive latency, frequent small updates, strong consistency, and simpler operations for GB–TB scale workloads. Distributed warehouses and lakehouses work better when you truly need massive multi-cluster concurrency or petabyte-scale patterns.